This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things

Contrary to the axiom we all learn in high school Economics, “There’s No Such Thing as a Free Lunch,” many things are, in fact, free. Sleeping, for instance, is free. I can’t remember a time when my pillow demanded I renew my annual subscription before tucking in for the night. Air is also free. So are sunshine, a good sneeze, smiles, and going outside to, as the kids say, “touch grass.”

Confusingly, there are also things that are:

(1) free but should not be free, like social media, web searches, and journalism;

(2) nearly free but should cost more money, like recorded music;

(3) used to be free but now cost some money, like booking fees for concert tickets or picking your seat on an airplane; and

(4) were never free but should be free or nearly free, like healthcare and education.

Things that used to be free that now cost some money and things that were never free but should be free or nearly free are all deservedly well-trod social, political, and economic debate fodder. But things that are free that should not be free, and things that are nearly free but should cost more money, have only recently become phenomena that we are becoming more attuned to as consequences both predicable but unintended consequences pile up around us and systemically change the way we interact with each other and consume information and entertainment.

The Original Sin of the internet was giving it away for free. Whereas Adam and Eve listened to the sneaky slithery boi in the Garden and eateth of the appleth, thus forever after corrupting Man for transgression against the word of God, we non-Biblical proto-humans gave away much of the internet for free in exchange for advertising, somehow both simultaneously transgressing against and supporting our new God, capitalism, which is seemingly also something only made possible by capitalism.

This is not to say that nothing on or about the internet should be free because it definitely should. Like baseline high-speed access to the internet itself as a public good subsidized by income taxes, email service, open-source software, end-to-end encryption, and videos of cats and bulldogs dressed in homemade knit costumes. These things should remain free as necessities of modern life and future innovation. Especially the knit animal costumes.

But we are also uncomfortably familiar with the phrase, “If a product is free, then you are the product,” and for good reason. Social media platforms (like the one you are likely reading this on), search products, and many news outlets, being the chief offenders of the our-users-are-the-product business model, all harvest our data and sell it onward to third parties, who sell it further downstream to fourth parties, and so on, so that we can then be targeted for the selling of other products and services that we don’t need but subconsciously (and statistically) might want, based on that harvested data. It’s a Sisyphean loop we will never see the end of unless we break it. And we absolutely can break it.

But we need to break it with our wallets.

Budgeting is tricky, and I’m no stranger to financial hardship. Despite my privileged appearance as a cis white man living in California - a genetic and geographic crime for which I shall never repent - just after graduate school in my mid-twenties, I was unexpectedly and unfortunately without any meaningful income and forced to live on other people’s couches for almost a year, an extended traumatic experience I hope not to replicate. So, I greatly empathize with people’s delicate budgets, including mine, and understand the need to keep costs down.

That said, theoretically, if we were all to pay a reasonable fee for select products and services, like social media, search, and the news, which we currently access for free, those products and services could run good and reasonably moral businesses without the data consumption and gag reflex regurgitation of that data that they currently do to run their not so good and questionably moral businesses. Would this solve the problem entirely? Likely not, but it would greatly alleviate it and remove the perverse incentive for more red-pilled rise-and-grind tech bros to build new “free” products and services that are purposefully designed to hold our attention and keep us engaged because their entire business model relies solely on our constant usage to mine and extract that much more data from us.

The evidence of the need for us to pay something for quality products and services that do not take advantage of us and to support the ongoing maintenance of those products or services is everywhere.

Our free apps constantly transmit location data, usage patterns, IP addresses, text inputs, and other seemingly innocuous data, like battery life, model of the phone, and operating system, to their developers. While all theoretically anonymized, all that data together creates identifiable profiles and predictive models of your future likely behaviors, sold into grey-area digital ad markets with customers like the Department of Homeland Security.

Our free social media feeds are no longer social. Open the free social app of your choice and try to find a single post from one of your friends in the endless scroll of advertisements shouting at you to buy something, like perfume sellers misting you with liquified garbage from a stall at the most ill-conceived shopping mall of our nightmares. Their sole real purpose is to generate the above data, along with additional data: our likes, follows, posts, re-posts, length of time we spend viewing, and our clicks. We should own or at least control that data, which is now being sold not just for ad dollars but also to train the next generation of generative AI models without our consent and on the backs of our years of accumulated digitally generated data capital.

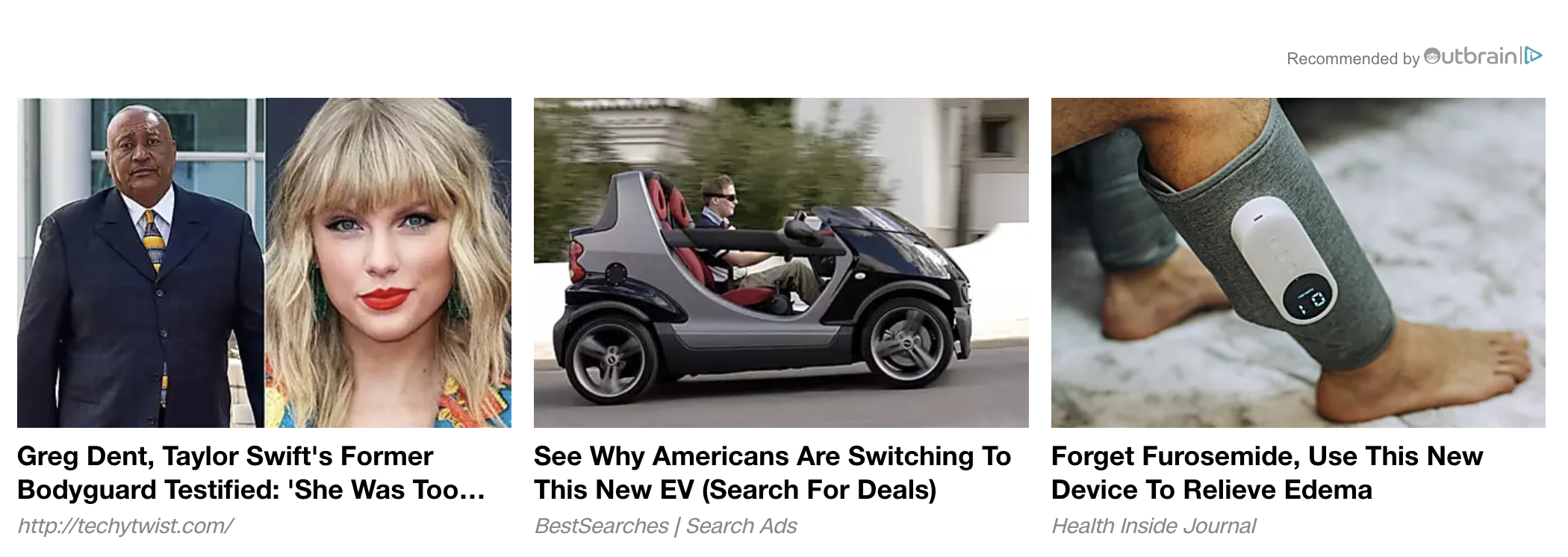

Our searches on Google are so diluted by AI-generated SEO-optimized click-bait garbage and sponsored content that it’s nearly impossible to find actual information from actual people absent searching for “How do I unclog my toilet” or “Why do people like the new season of True Detective even though it sucked” without appending the word “Reddit” to the end of the query so that you are ensured real results from real people with real advice or opinions.

Our news is becoming diluted, polluted, and, in many cases, non-existent as mass layoffs deplete the newsrooms and journalists doing quality and necessary work that preservers democracy as the Fifth Estate. Horrendous advertising blocks fill the spaces where we consume news, often obfuscating what is news and what is an advertisement. Even as I was working on this piece, VICE, as a going concern, shut down its website and news operations because it was no longer deemed worthy (read: profitable) to keep it open post-bankruptcy, thus depriving the world of some of the best and most hard-hitting investigative technology and cultural journalism that is not covered by more mainstream news sources.

News (and writing in general) is not meant to be this ephemeral and fleeting. Researched, reported, published, posted, and then relegated to history, essentially hours later, and in the case of failing journalistic enterprises, often deleted from history entirely. You can still read half-decayed papyrus scrolls from a thousand years ago or go to any public library and look at microfiche like a trauma-laden detective in a David Fincher movie. And yet, you can’t read some genuinely excellent journalism from just five years ago because the news entity that published it collapsed, and no one was left to pay for the servers that stored the pieces.

We have a collective action problem that we would all benefit from solving but have so far been unable to admit it exists. The bad actors are not the problem. We are the problem because we enable them.

We have become so accustomed to this imbalanced transfer of capital, where our attention and data are the capital being transferred in exchange for access to products and services, that we put up with it and scoff when anyone dares put up a paywall, even a marginal one. When a product or service costs some amount of money, as all real-world tangible products and services do off of the internet, most of us will opt to take the “free” version in exchange for our data and ads for shit like this which I just now screenshotted (screenshot?) on the home page of CNN.

We need to collectively become more attuned to and suspicious of what we get for free and question whether or not there is a better alternative that may cost some amount of money. I also fully realize that “Go Buy Stuff!” conjures uncomfortable memories of what Americans were weirdly asked to do in the aftermath of 9/11, and I am not suggesting that we evolve into downward-bent-neck zombie consumers slaving away to earn more money for the sole purpose of gobbling up whatever shiny new toy is dangled in front of us on our black mirrors. But if more people were to take the approach not of “Go Buy Stuff!” but instead the approach of “Maybe, Go Buy Some Things Which Are Within Your Budget And Add Value To Your Life And The Lives Of Those Around You Without Causing Greater Societal Harms” we would at least begin to shift the Overton Window on what is acceptable behavior in the development of digital products and services.

If we can shift our mindsets, we can collectively overcome the now-standard belief that every new digital business must aspire to become a “unicorn” (a startup that becomes a $1 Billion valued company) with 1 billion users and a logo identified around the world, a bizarre phenomenon that I have witnessed for well over a decade working in the technology and startup world where everyone thinks they will be the next world-famous billionaire who “disrupted” a part of the economy that didn’t need to be disrupted by selling an AI self-affirmation mirror. And yes, that is a real thing.

This endemic and perverse mindset comes solely from the need to reach an unfathomable scale of users to generate enough data to monetize on and eyeballs to sell to. You cannot walk down one block in San Francisco without finding both a steaming pile of shit and a man in a Patagonia vest who stands in front of their (self-affirming AI?) mirror each morning, saying to themselves, “I am the next Steve Jobs.” Oh, wait, both of those things are steaming piles of shit; my mistake. A healthy free market economy is not one with rapaciously designed products and services all vying for our attention because our attention is what they need to exist. A healthy free market is one where many different businesses exist, perhaps each offering the same or similar products and services, each with its own set of customers, each charging for the cost of doing business plus a sustainable profit margin and the potential for growth according to the principles of competition via user preference of the quality of the product or service offered by the respective business.

A healthy free market economy is not one with rapaciously designed products and services all vying for our attention because our attention is what they need to exist. A healthy free market is one where many different businesses exist, perhaps each offering the same or similar products and services, each with its own set of customers, each charging for the cost of doing business plus a sustainable profit margin and the potential for growth according to the principles of competition via user preference of the quality of the product or service offered by the respective business.

The things that are nearly free but should cost more money are a bit tougher to unpack than things that are free but should not be free. I have been a music fanatic in every sense of the word for my entire life. I would have willingly committed first-degree homicide of a blood relative if you had told me at age fifteen that I could have a real-life Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy in my pocket with infinite music forever in return for my intentional parricide.

We take for granted every day that we can (almost) any song ever recorded out of thin air. Streaming is effectively black magic. Magic because it truly is magical to randomly remember that you used to listen to Tom Petty with your dad a lot as a kid and be belting out “Learning to Fly” seconds later, much to your wife's displeasure, at 8 am on a Sunday, which may or may not have happened recently. But it’s black magic because we have struck a deal with the devil. We can have all the music in the world, but the artists who make it will not be fairly compensated.

During my freshman year of college, I gained access to high-speed internet for the first time and, consequently, torrents. Private communities like Oink, Waffles, and, in the words of Trent Reznor, the “Library of Alexandria” of music known as What.CD, gave me access to an embarrassment of free music riches, in the highest quality possible, vetted by the nerdiest and exacting audio nerds. Spanning multiple hard drives and literal years of consecutive listening time, I was able to engage in a voracious study of the history of recorded music, along with every Best New Music drop from Pitchfork, as I shelved books for otherwise silent and tedious hours at my university library job over four years.

But I knew I was stealing the great art of great creators, and in kind, out of a sense of obligation and duty, I gave back and gave back many, many times over in my attendance of concerts and festivals and buying of merch. The great irony is that this is precisely how most artists have come to make money, given the insubstantial income they now generate from streaming royalties. It is exceedingly rare, if not outright impossible, for a modern artist to survive on streaming income alone, seemingly unless you are Burial.

But before those heady days of piracy, I, and everyone else in society born before the advent of digital music and streaming services, once paid comparably very high prices for recorded music in physical form. Distribution of that physical media wealth aside, as much of that wealth went to the major record labels as it still does today, it was much easier to make a living as a talented recording artist because artists still received a more significant cut of those marginal payments on physical recording sales than they do off the pittance of a fraction that they currently earn from streaming.

If we love music, we need to pay for it, one way or another.

Only subscribing to streaming services for slightly more than $10 a month does nothing to keep the industry healthy with a thriving musical middle class of working musicians, which currently no longer exists. There are only the haves and the have-nots in music, the superstars who either earned their stripes and wealth many years before the digital age, or the increasingly rare new superstar propelled to fame by random TikTok virality, or even rarer, unique talent discovered at the right moment by pure luck.

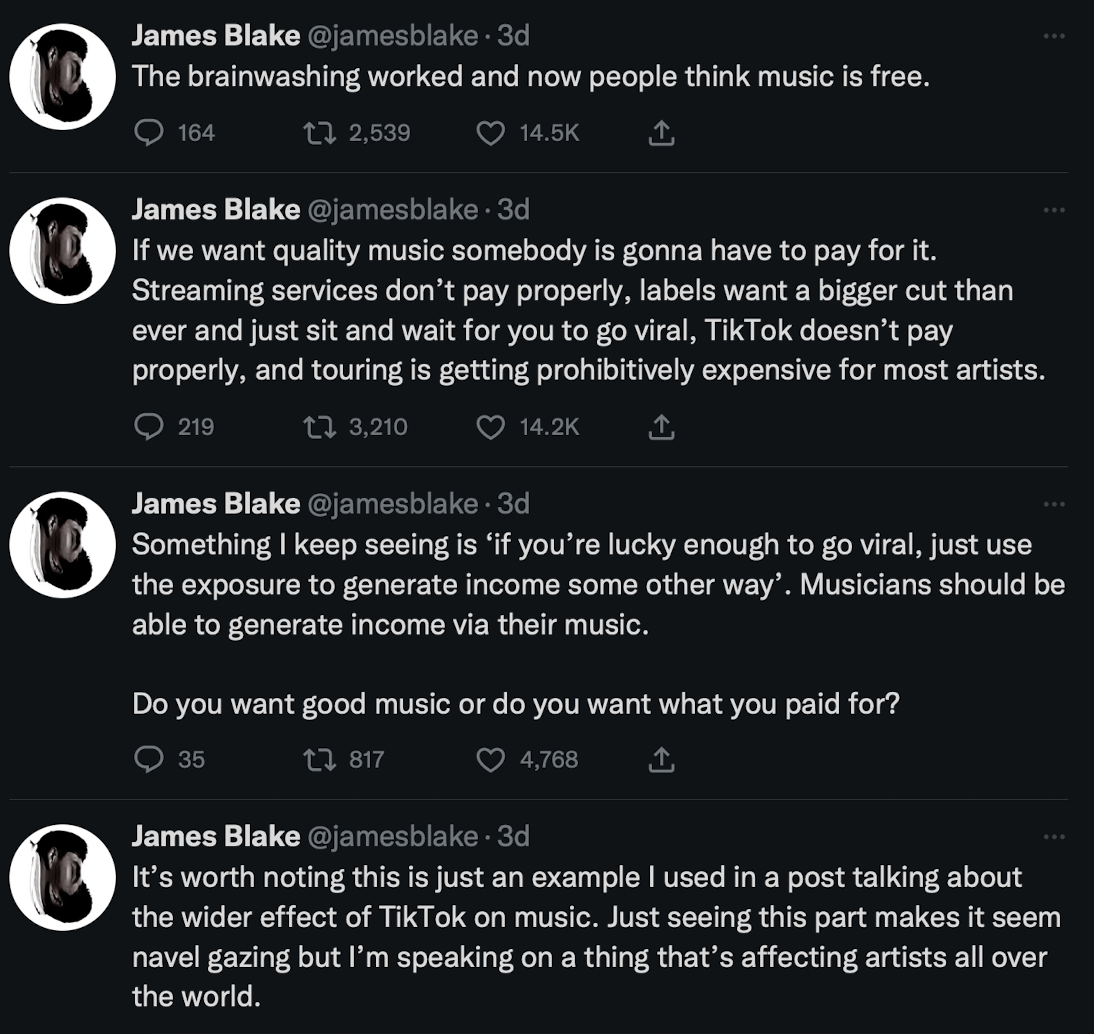

While I was getting ready to publish this a few days ago, the inimitable James Blake, an artist I have loved and admired for many years, and not just because he is exceedingly tall and handsome, made some very strong statements that echo and articulate the state of affairs in music economics in almost precisely the same terms I wrote here.

We need to become more comfortable with no longer just getting all the music in the world for what is essentially free and consciously think of other ways to support artists, like attending concerts and buying merchandise or physical media directly from the artists themselves. While the concert business is thriving, the music itself has become somewhat of an advertisement, a calling card, for the live experience. Performing live through endless touring is how most artists are now forced to earn their living because their recorded music is worthless, and to have a reason to tour, you have to put out new music constantly. This endless touring and recording cycle takes a massive toll on performers’ spiritual, bodily, and mental well-being, and it’s well-documented how many performing artists suffer for their art out on the road. This level of commitment to live performance is not sustainable, and our favorite independent musicians regularly burn out from the necessity to play shows constantly out of a need to feed themselves and their families.

It is somewhat optimistic to at least see an openness by some powerful and entrenched institutional forces like the major labels and some streaming platforms to try different business models that reapportion the streaming shares that go to artists. However, no model has even been remotely successful or widely implemented yet. However, such things are merely laboratory experiments and are being done in relatively small-scale trials.

The arguments pointing to significant problems with the devaluation of music often only point to large corporations like streaming services and the major labels as the sole perpetrators of the washing out of the musical middle class. These arguments occur daily in the major music periodicals, on the artist-formerly-known-as-Twitter, and amongst musicians everywhere. It is easy to blame “the man,” in this case, “the man” is certainly not without blame.

I want to posit another perpetrator. Me. Us. The fans of music.

Despite “patron of the arts” being a description that brings to mind exceedingly wealthy individuals with monocles, supporting galleries and painters from high in their opulent penthouses off of Central Park, it’s something we need to all start thinking of ourselves as. If you are a fan of something, consider being a “patron” when possible.

Really into the first album from a new band you have never heard of before? I can guarantee you that a $20 t-shirt off their website will buy someone lunch out on their first tour.

Have you been listening to a label for years that consistently puts out quality releases? See if they sell some stickers or hats.

Even if you don’t have a record player, pick up a vinyl record directly from an artist or label once in a while to stare at the artwork and hold the album in your hands, just to remember that music is not meant to be disposable and that it does mean something greater when we don’t treat it that way.

All I am asking for anyone to do is do what they can when they can, which is all anyone should ever be asked to do. Whether it’s social media, search, journalism, or music, if we want nice things, we should probably start thinking about paying for them.

wtflolwhy :: March 5, 2024